How I Track Weightlifting Progress (Without Maxing Out Frequently)

Posted on Sun 13 September 2020 in Fitness • 7 min read

Working With Different Rep Ranges

Weightlifting progress is almost always discussed using the most weight you can lift for that particular exercise for a single repetition. This is usually called the "one-rep max", or 1RM. Attempting an actual 1RM lift is very mentally and physically taxing, so most of my training and workouts involve a much lower amount of weight for multiple repetitions per set for multiple sets per workout. Since I haven't competed in weightlifting, knowing my own personal 1RM for each lift is mostly used for calculating the weights used in each workout.

Since I've been using the 5/3/1 program by Jim Wendler for a few years now, I've become a big believer in using submaximal weights for higher reps and more sets. I've used different variations of 5/3/1, but my typical workouts involve 6-12 sets of the main lift, with each set consisting of 5-10 reps. Rarely I will go below 5 reps, and usually once per year I'll do a test of my 1RM. In between these tests, I want to make sure I'm making progress so my next 1RM will be higher (because I like seeing numbers go up).

Evidence of Weightlifting Progress

Judging weightlifting progress can be a tricky thing due to the number of variables involved, including sets, reps, volume, weight lifted, and the bodyweight of the lifter. Quantifying this progress is important for both motivational purposes and for data collection. This data can be used for evaluating how well a particular workout program or phase is working for strength. It can also be used for projecting milestones, but it's hard to predict plateaus or resets, so this must constantly be adjusted.

Most of my workouts involve a "top set" of the main lift of that day, which is the highest weight used for that workout. When trying to compare a given set to a previous top set to see if there was a strength increase, there are a few ways to see progress:

- Weight lifted has gone up for the same number of reps at the same bodyweight

- Weight lifted is the same, but the number of reps has increased

- Bodyweight is lower, but can lift the same weight at the same number of reps

- Same weight, same reps, same bodyweight, but more volume was lifted prior to that set (as in, I was already tired)

- Same weight, same reps, same bodyweight, same volume, but the lift "felt easier"

Of those 5 ways to see progress, I really focus on the weight and the reps as my main sources of data for absolute strength, with bodyweight as a secondary data point for broader trend tracking and motivational purposes. I track the volume and number of sets I completed before and after this top set in my notes, but it's much harder to quantify how this affected the top set so I generally don't use it in any calculations. I also tend to ignore the "felt easier" aspect, since almost all of my top sets "feel heavy" and "are hard".

If just the weight or reps change, it's pretty clear which lift was better. But what if you squatted 300lbs for 7 reps, then you squat 330lbs for 5 reps? It becomes much harder to know if that was progress or not.

Calculating An Estimated 1-Rep Max

The easiest way I've found to compare two different sets with different weights and different reps is to calculate an "estimated 1-rep max", or e1RM. The formula I use for this is:

( Weight x Reps x 0.0333 ) + Weight

For the example above, a squat of 300lbs for 7 reps has an e1RM of 369.93lbs, while a squat of 330lbs for 5 reps has an e1RM of 384.95lbs. This makes it easier to compare the two sets to see the level of progress. When doing cycles of lower to higher weight and from more to less reps, it can be valuable to do this conversion.

One thing I found out the hard way is that these estimated maxes aren't 100% accurate. I've taken my estimated max for a lift and tried to perform that for one rep, and it hasn't gone well. I think one main factor for this is that calculating your estimated max from a 2-rep set is very different from a 10-rep set. The other main factor is that it is a different skill to perform a lower weight for 10 reps in a row than to perform a maximum weight for a single rep. Failing your tenth rep means you still did 9 reps, while failing your 1RM attempt means you didn't get any reps. That said, I still find it useful to have these e1RM numbers, but I make sure to keep in mind that I don't assume I could hit that on any given day.

Tracking Monthly And Yearly Trends

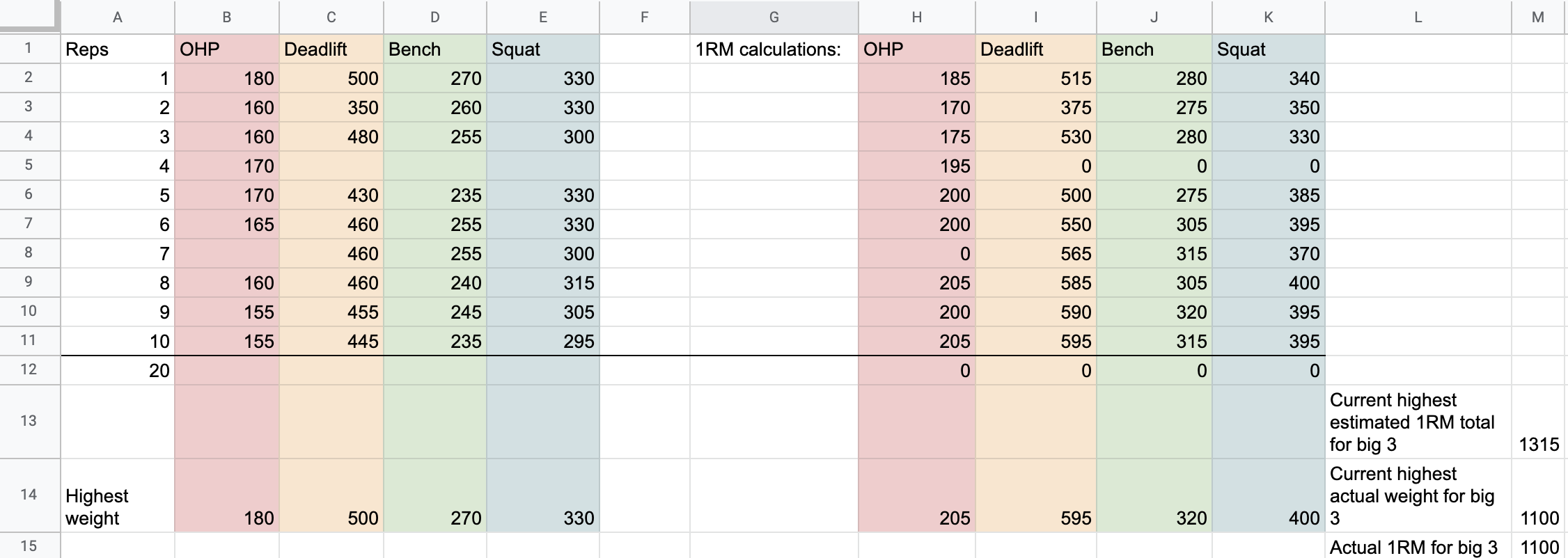

Now that I have a single number that I can convert all of my sets to for any lift, I can track that e1RM over time to judge progress. In my spreadsheets, I split things into each main lift to track separately. For me, this is the overhead press, trap-bar deadlift, bench press, and SSB squat. For each lift, I keep track of the most weight lifted for 1 rep, for 2 reps, for 3 reps, and so on up through 10 reps. For each of these set maxes, I calculate an e1RM and round to the nearest 5lbs.

From here, I can now keep track of the most actual weight I've lifted in each month, and the highest e1RM I achieved each month. I do this monthly, since my workout plan goes in 3-week phases and overall weight increases happen in each new phase. I find that the monthly trends make it easier to see progress, instead of worrying about workout-to-workout fluctuations. I also track my average bodyweight that month for better correlation and smoothing of bodyweight fluctuations. Finally, I add up my bench press, deadlift, and squat numbers into a single "powerlifting total" (even though I don't compete in powerlifting). This leaves me with a monthly single number for max weight lifted across the 3 powerlifting movements, a monthly e!RM number, and a monthly bodyweight number.

![]()

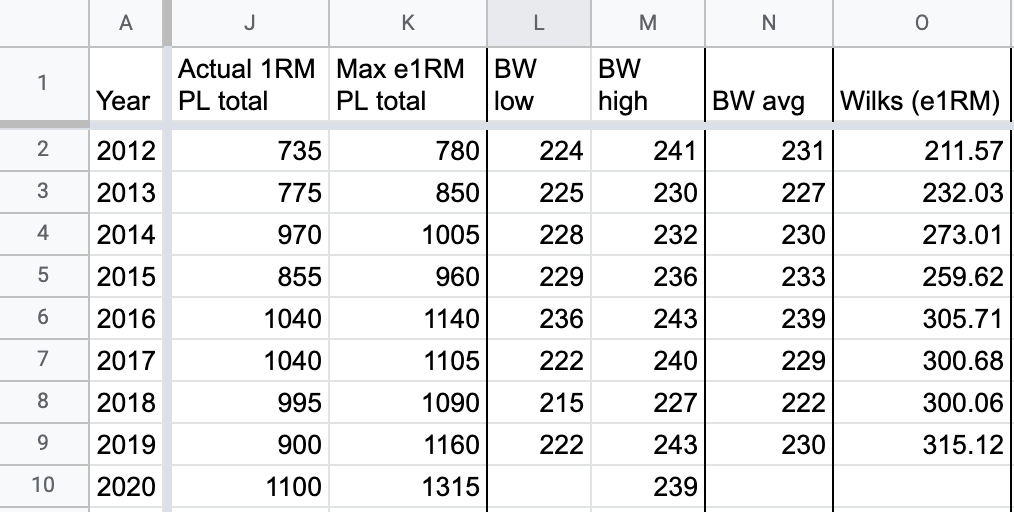

I have a separate tab that I use for storing the yearly maxes for all of these numbers as well. Seeing these yearly trends after accumulating a few years of data helps show the progress I've made and really helps motivate me to keep pushing and stay consistent. The monthly numbers are then good indicators that I'm making steady progress and alerts me if I need to change anything.

Bonus: Calculating A Wilks Score Using Bodyweight

In powerlifting, there is a calculation called the Wilks Formula that computes a single number based on your bench press max, deadlift max, squat max, and bodyweight. The idea for this is to be able to compare a 220lb lifter to a 210lb lifter to see relative strength. This has gained favor over the more traditional weight class approach, as anyone who is at the bottom of a weight class has a disadvantage to someone at the top of a weight class.

Since my bodyweight doesn't change all that much month-to-month, but it does year-to-year, I've started calculating my Wilks score based on my average bodyweight for the year and the max e1RM for that year. I know full well that this is a weird way to use the Wilks number, as it's typically calculated based on your bodyweight and lifts for a single day. That said, in spite of knowing that it's not a true number, it does help for me to compare year-to-year trends in my strength by boiling it down to a single number.

Benefits of Data Collection and Tracking

Overall, I find that tracking my sets, reps, and weight in each workout helps me see how any individual workout went. If I'm going into a exercise where I'm going to do my top set for as many reps as possible (also called AMRAP), I can use my e1RM calculation spreadsheet to see how many reps I would need at the prescribed weight for that day in order to set a new e1RM record. Having this goal for reps in mind helps me push myself harder than I normally would to make sure I'm making progress.

Monthly trends of both raw weight lifted and e1RM numbers help me see how well my workout program is going. Sometimes, changes are so small that I don't even notice, but I can look back to prior months and see that those small changes have added up to some noticeable strength improvements. Yearly trends show this on a broader scale, and also helped show me that I was hitting large plateaus that were likely caused by low testosterone. Having this data has not only motivated me, but also alerted me to health problems. Even when I was lifting relatively little weight, I'm glad I kept this data to show these trends over time.